|

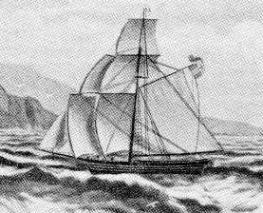

On July 4, 1825, the first group of emigrants from Norway to America set

sail on "Restauration", a sloop that later became known as the

"Norwegian Mayflower". Descendants of those brave souls

became known as Sloopers.

I am a member of the Norwegian Slooper Society of America,

an organization founded in 1925 and patterned after the Society of

Mayflower Descendants. The membership includes descendants of the

original Sloopers and their spouses. The name was derived from the

fact that the Norwegians have always been great discoverers and settlers going back to Gunnebjørn discovering Greenland in 876, Marsen discovering and settling the Chesapeake country in 983 and Huerjulfsen sighting our northern coast in 986. Leif Erickson landed in Massachusetts in 1001 and Norsemen lived there for 60 years. In 1362, 22 Norsemen penetrated America from Hudson Bay as far south as southern Minnesota. But with the Sloopers of 1825, immigration from Norway to America began in earnest. In the early years of the 1800s, some Norsemen were suffering persecution by the established Norwegian Lutheran church if they didn't abide by the strict laws set down by them. Everyone had to pay duties and taxes to the Church and was fined if he didn't act according to the Church's rules. This was the main reason for the Sloopers wanting to leave Norway. There were others though. The economic situation was bad and the future looked grim for their children. This was due chiefly to the scarcity of land. Of the total area of Norway, 60% is nothing but bare mountains and 30% more is forests, bogs, and ice. Only about 3% can be cultivated. Yet during the period before the Sloopers left Norway, 95% of the population was trying to live off the land. A bonde (a farmer owning land) with more than one son had to divide his farm among them to provide them with the means for sustenance. The farms had been divided so much during the preceding years that they were too small to support a family. So we find, out of the 52 who were to depart from Norway, 27 were believed to be religious dissenters and the other 25 were mainly discontented farmers. There were 15 children and two pregnant women. Two men, Cleng Peerson (or Pedersen) and Knut Eide, were sent to America in 1821 to investigate the possibility of religious freedom and economic prosperity. Knud Eide became ill after his arrival and died, leaving Peerson alone to examine the country and learn about the customs, laws, language, and agriculture. He probably traveled as far as the western counties of new York state, as the Sloopers were first settled in Kendall Colony, a village about 32 miles northwest of Rochester. Peerson returned to Norway in 1824 with a report that was very favorable, so many of the Sloopers began making plans for the trip. Once the decision was made to go, Peerson was sent back to America to buy land and prepare for the arrival of the immigrants. His companion this time was Andreas (or Andrew) Stangeland. After their arrival in New York, they traveled to the northwestern part of the state where they purchased six pieces of land, which was to be held for them until the fall of 1825. Peerson also built a house there, about 20 x 24 feet in size, in anticipation of the Sloopers' arrival. All of this news was sent back to Norway by letter. In Stavanger, Norway, the Sloopers began their final plans which included the purchase of the sloop Restauration. This sloop was brought into the harbor at Stavanger on May 9, 1825, where it had to be remodeled to accommodate 52 people. Berths had to be built for all of them on the lower deck, but there was only 250 square feet available for sleeping. Even with double bunks, this was less than two-thirds the room needed for 2.5 x 6 foot bunks for the immigrants. These bunks were built in tiers of three or four and the poor passengers had to worm their way in and out like eels. The children probably shared bunks toe to toe. Also, space had to be provided for the chests containing their possessions and provisions. Each family was allowed one chest which was about 2.5 feet wide, 2 feet high, and 5 feet long. Everything else had to be sold, often a heart-breaking problem. Possessions that had been in the family for generations had to be put up for sale or given away. As for the living and eating space, it was only about 6 inches above their heads up on deck, where there was a galley for cooking food and tanks for fresh water - enough to last 52 people for 2 months. There were also lockers to hold fuel for the stove, extra canvas for sails, ropes and other sailing gear. Every family brought food that would keep - cheese, flatbrød, rye bread, cookies, dried beef, salt pork, smoked and dried fish, and dried fruit. For drink, some brought kegs of home-brewed ale, sour milk, tea and some coffee, which was not common throughout Norway then, although it was used in the coastal districts. In the hold they carried 3.2 tons of Swedish iron for ballast and profit, expecting to sell it upon their arrival. Swedish iron was well known for its excellent quality and had a wide market. In order to comply with the navigation laws and proper clearance papers, it was necessary to select and register a crew. The captain was Lars Olsen Helland and the mate was Peder Erickson Meland. Five of the immigrants agreed to make up the balance of the crew, ranging in age from 15 to 25. And so, on July 4, 1825, the sloop was officially cleared for sailing with 45 passengers and crew of 7. As they sailed out of the harbor at Stavanger displaying their new flag, many people waved and the battery at Kalhammer fired a salute. A great-granddaughter of one of the Sloopers, many years later, wrote the following poem:

This is the first half of the story and is from the book The Sloopers, Their Ancestry and Posterity written by J. Hart Rosdail, a descendant of a Slooper. |

tiny ship Restauration, now known as the Norwegian Mayflower, was

a sloop, a small sailing craft 54 feet in length and 16 feet in breadth.

tiny ship Restauration, now known as the Norwegian Mayflower, was

a sloop, a small sailing craft 54 feet in length and 16 feet in breadth.